I was recovering from a very sprained hamstring, which I had suffered whilst playing football back in Jakarta, so I sat alone, except for the shaman and his family, and put down my thoughts for our guide Tonik's testimonial book.

It was a gruelling week for me; my glasses steamed up constantly in the humidity of the forest and it rained every day. This meant that our overnight sleeps in the uma (settlement longhouses) were in dry clothes with our wet gear being re-donned the following mornings as we prepared to trek on. My pulled hamstring had been only a minor handicap, but the trek didn't aid its recovery.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Never again, I say, only half in jest.

But I?ll never forget.

We are still in touch with Tonik, a Minang, and I hope our mutual respect and co-operation continues as Hotel Rimbo gets off the ground. Ask for him in Bukittinggi.

You're a Friend of the Rainforest, but until now you've confined your involvement to demonstrations and petitions. But that's in your cities and towns.

Go trekking with Tonik through the rainforest of Siberut and discover just what it is that you've felt passionate about.

The torrential rain, the mud and slime, the tree trunk pathways you'll fall off, the leeches that suck, the thorns that sting and the spiders - the big spiders - that jump.

It's then that you'll ask yourself - why?

For me, there's only one answer - the people.

Whilst we cannot adapt ourselves to life in the forest - and we've got backpacks, Swiss army knives, strong shoes, a book for bedtime and a torch to read it by, and we've also got strong porters to carry our food for the week, bedrolls and mosquito nets - the Mentawai have had c.4,000 years to find their balance and harmony.

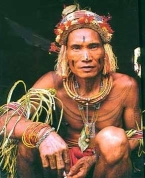

We were privileged to share their life for a few days and to be part of a fairly rare communal celebration, the initiation of a new medicine man/shaman.

You've read that tropical rainforests are the repository of untold wealth in terms of future drugs for the benefit of sufferers from all manner of diseases. Whilst we have access to modern science, scientists are rapidly reasoning that we need to go back in order to step forward.

What we witnessed - and became participants in as family guests - was the culmination of six months of formal preparation and a lifetime, nay, several generations-worth, of experience.

To describe is to formalise. The symbols had their place and their meaning. So did the dances and trances, and the slaughtering of three pigs in honour of and for the three sponsoring shamans from neighbouring, i.e. somewhere on Siberut, villages.

We were told, Tonik told us, that each dance focussed on an aspect of forest life. Each plant, each animal, each facet of village life was celebrated by the four shamans, occasionally supplemented by an older woman - the women generally stayed in a separate room - or a young man dressed in T-shirt, who danced in an anti-clockwise moving circle whilst stomping their feet in unison, with accompaniment provided by 2 or 3 hand drums and a clanged piece of iron. Basic rhythms from dusk to dawn. Those of us who vainly tried to sleep weren't allowed to for long.

What it meant for the Mentawai was sharing and caring, and a reinforcement and, thereby, a continuation of a life under threat, yet slowly changing.

You see, we came and have fleetingly passed by toting our baggage and preconceptions. The younger generation now sport western-style clothes and shun tattoos. We flash by with our instant photos and leave our traces. I left some holograms cut from expired credit cards (which were worn as pendants on the shamans' necklaces). Others have left keys and keyrings as similar adornments.

In a land where time is measured by sunlight and moon phases, some sport watches, which don't actually work. Safety pins dangle from ears and loin cloths, made from leaves, bark or old cloth, cover the nether regions.

The Mentawai have no one God because every living thing has its place in their world. As I write this sentence, one of our porters who attends elementary school in the government village of Madobak shows me her school textbook - How To Be A Muslim.

But, she tells me, she still eats pig.

Change will come. We are part of that process. We must be sensitive and appreciate and respect the integrity of these people. Our baggage is ours.

We cannot live as they live. But, like them, we can be generous in spirit and demonstrate respect for each other through a degree of sensitivity towards their life.

These people are not picturesque, although we sought and received permission to take photographs. We are the curiosities with our curiosity. What we leave behind must be of benefit or, negatively speaking, of limited damage.

Many thanks to Tonik for his sensitive guiding. I trust we will be fondly remembered by the Mentawai. I can't say that the newly initiated shaman fixed my pulled hamstring but in letting him try and later dancing with another, I hope this is so.

Footnote

Jakartass has been given a plug by Gadling, a blog - an online magazine - about "engaged" travel.

Amongst their links, there is a fascinating online article of 8 pages about an Ubud, Bali, based outfit which organises tours to Papua. It makes fascinating yet, in the light of what I have written above, disturbing reading.

The Selling of the Last Savage

On a planet crowded with six billion people, isolated primitive cultures are getting pushed to the brink of extinction. Against this backdrop, a new form of adventure travel has raised an unsettling question: Would you pay to see tribes who have never laid eyes on an outsider?